Background and My Previous Research

Endogenous and exogenous DNA-damaging factors, such as free radicals caused by oxidative metabolism and collapsed replication forks or environmental mutagens and natural radiation, pose a constant mutagenic threat. The DNA damage response (DDR) comprises proteins that sense DNA damage and mediators that transduce the signals to effectors that ultimately coordinate cellular events such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, and differentiation. Interestingly, the DDR varies by damage, cell cycle and cell type.

Double–strand breaks (DSBs) represent the most toxic form of DNA damage (and therefore also the most attractive for cancer therapy). They are repaired by two major pathways, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homology directed recombination (HDR). DSBs lead to the activation of a pathway initiated by the apical protein kinase ATM which phosphorylates hundreds of effector proteins, particularly the checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) and the tumor suppressor p53. Chk2 and p53 regulate both the G1/S and the G2/M arrest. DSB processing can also lead to RPA-coated single-stranded DNA and the subsequent activation of the ATM-related kinase ATR. An important downstream target of the ATR pathway is Chk1.

Endogenous and exogenous DNA-damaging factors, such as free radicals caused by oxidative metabolism and collapsed replication forks or environmental mutagens and natural radiation, pose a constant mutagenic threat. The DNA damage response (DDR) comprises proteins that sense DNA damage and mediators that transduce the signals to effectors that ultimately coordinate cellular events such as the cell cycle, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, and differentiation. Interestingly, the DDR varies by damage, cell cycle and cell type.

Double–strand breaks (DSBs) represent the most toxic form of DNA damage (and therefore also the most attractive for cancer therapy). They are repaired by two major pathways, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) and homology directed recombination (HDR). DSBs lead to the activation of a pathway initiated by the apical protein kinase ATM which phosphorylates hundreds of effector proteins, particularly the checkpoint kinase 2 (Chk2) and the tumor suppressor p53. Chk2 and p53 regulate both the G1/S and the G2/M arrest. DSB processing can also lead to RPA-coated single-stranded DNA and the subsequent activation of the ATM-related kinase ATR. An important downstream target of the ATR pathway is Chk1.

The transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 4 (KLF4) is an important regulator of cell fate decision, including cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and stem cell renewal. KLF4 is activated by ionizing radiation (IR). KLF4 can induce both antimitotic and antiapoptotic genes and plays an ambivalent role in tumorigenesis as a tissue specific tumor suppressor or oncogene.

During my PhD studies, I focused on the role of chromatin in p53-dependent transcription. During my postdoctoral studies, I studied the role of KLF4 stability in colon cancer formation, the regulation of DNA replication by ATM as well as the function of ATR in the response to ionizing radiation. My goal is to combine my expertise in chromatin and transcription, cell cycle regulation, and the DDR to study important questions in cancer biology, particularly on genomic integrity.

Projects in the lab

The mechanisms of ATR kinase-dependent radio- and chemosensitization

ATM and ATR are apical kinases of signalling cascades initiated by DNA damage. For two decades scientists have considered ATM to be the best drug target for radiosensitization because ataxia telangiectasia patients, who express no ATM protein, are the most radiosensitive humans yet identified. Using reverse chemical genetics we showed that transient inhibition of ATR kinase, using recently identified selective and reversible small molecule inhibitors, increases IR-induced cell death to a bigger extent than ATM inhibition. Furthermore we discovered a novel function of ATR in G1 phase and an amazingly strict and unpredicted temporal requirement for ATR kinase activation following DNA damage. This capacity to block repair by exposing cancer cells to a short treatment with drugs that target key components of the DNA damage response has significant clinical potential and we currently test ATR inhibitors and other drugs targeting the DNA damage response in preclinical models.

The DNA Damage response and Cancer Cell Plasticity

Recent advances in radiation therapy, such as image-based planning and directed delivery, have led to enhanced clinical outcomes. Unfortunately, local recurrence and metastasis remain a great problem due to failed eradication of tumour initiating cells. This subpopulation of cancer cells, also termed cancer stem cells (CSCs), has been reported to have higher self-renewal potential, increased DNA repair capacity, greater metastatic potential, and also increased resistance to genotoxic stress (such as ionizing radiation and chemotherapy) compared to bulk cancer cells. We investigate both the origin of these CSCs, the mechanisms underlying their treatment resistance, and the mechanism of their plasticity in vitro and in vivo, with the aim to find both better treatment modalities and gain insight into cancer etiology.

Therapies targeting Cancer Stem Cells to inhibit metastasis

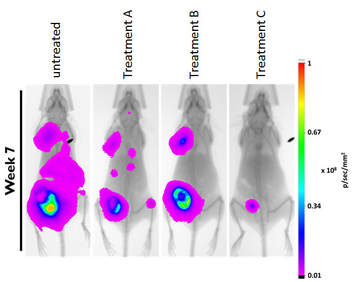

Most cancer mortalities are due to metastases, not the primary tumour. Only a subset of cancer cells are CSCs. But because of their high cell plasticity (see above) and their tumour initiating capability, CSCs are considered the main culprits of metastasis. In order to prevent local recurrence and cancer spread it is therefore essential to not only target the bulk of the cancer cells, but to eradicate these CSCs. Two years ago with started a novel approach to target them and our efforts have led to very promising results in our preclinical mouse models (shown is an orthotopic breast cancer xenograft model, cancer cells are visualized by bioluminescence).

Identifying drug targets and biomarkers in DNA damage response pathways

During tumourigenesis cells often lose DNA repair mechanisms leading to increased mutagenesis. These DNA repair defects and/or the increased replication stress make cancer cells heavily dependent on the (remaining) intact DDR pathways. Radiation and most chemotherapies attempt to kill cancer cells by eliciting DNA damage. Combining these genotoxic treatments with drugs that target specific DDR pathways critical for cancer cell survival promises to selectively increase tumour-specific cell death. Such chemo- and radiosensitizers can target DNA repair proteins or, as we showed in the case of ATR, signalling proteins that regulate repair and check points. The aim of my lab is to identify further proteins involved in the DDR that can serve as a) drug targets and b) predictive markers. In particular we will use our extensive expertise in protein complex purification and targeted proteomics to identify novel interaction partners of key components in the DDR.

The role of chromatin in DNA damage signalling

Chromatin plays a key role in modulating the DNA damage response. Heterochromatin was not only found to slow DNA repair, but the chromosomal context of DNA lesions seems also to influence the signalling response. A fine regional balance between chromatin decondensation to allow access to DNA repair factors and retention of chromatin organization to protect genome integrity are essential for an effective DNA damage response. This requires an intricate cross-talk between DNA damage sensors, chromatin and chromatin modifiers. Indeed, covalent modifications of chromatin, particularly histones, are also used for relaying the DNA damage signal. In collaboration with the neighbouring lab of Dr. Hendzel we are investigating the players involved using cutting edge biochemical and cell biological tools. Projects in the lab include the development of novel methods to study the processes at sites of DNA damage.

(for references see "Publications")